Can Cryptocurrency Replace Central Banks?

- The topic of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) is slowly becoming one of the hottest financial debates.

- Cryptocurrency often comes up as a potential solution for CBDC, some even arguing that it will eventually replace central banks as a whole.

Federal Reserve building in Washington, DC. Thomas Barrat/Shutterstock

Table of Contents

Central banking often gets a really bad rap, being portrayed as the pivotal point of a modern type of slavery. In that context, cryptocurrency repeatedly comes up as the solution to the central banks problem. As a decentralized digital currency, not controlled by a single entity, public blockchains and their digital assets seem to be a representation of a better future, one that eradicates central banking and brings back monetary control in the hands of the people. However, is that actually the right way to look at it?

When central banks came to be

Even though the U.S. Federal Reserve was established in 1913, the concept of central banking was far from revolutionary at the time. In 1609, the Netherlands was the first country to implement a central banking system, transforming the nation into a global power. In 1694, England followed the Dutch example and created their own central bank, which later became the core of the might of the British empire.

The U.S., although independent since 1776, didn’t implement a fully functioning central banking system for more than a century. However, the one established in 1913 was not the first try. Two previous attempts at establishing a central bank failed – one in 1791 and one in 1816. The first one failed after 20 years of activity as Congress refused to renew the charter. In 1816, the charter was renewed, but again ran for 20 years and failed to get renewed.

For the years leading up to the creation of the Federal Reserve, the U.S. used various banking systems to try and keep the economy stable. None of them proved effective.

Why create central banks?

The relatively complex structure of the Federal Reserve is part of the reason why it has been a central participant in countless conspiracy theories, most of which portray the establishment as a form of forceful governing entity with the sole purpose of helping those in power stay in power. However, the truth is not as rudimentary as many think.

While the Federal Reserve certainly has its flaws, often the focus of financial debates, it has been instrumental to the evolution of the banking system, as it transitioned from gold-backed bank notes to a purely fiat currency-based economy.

Prior to the implementation of the Federal Reserve, the U.S. economy was, on a regular basis, bashed by banking crises:

The one that forced the leaders at the time to say enough is enough was the Panic of 1907. Although all these events were triggered by unique circumstances, they were all the result of a fundamental human emotion – fear. As rumors spread that a bank was insolvent, everyone would panic and withdraw their money, making the rumor, however true or untrue, a reality. That’s what’s called a bank run.

Soon afterwards, other banks, seemingly in a healthy state, would also suffer from the panic as people’s fears grew out of control and everyone withdrew their money to hide them under mattresses, thinking that if one bank failed, other banks would most certainly follow. And since there was no central bank to save the day as the Federal Reserve did in 2008 in a controversial move some still think was unnecessary, these monetary panic events got progressively worse, merely backed by word of mouth.

This classic example of a negative feedback loop is at the core of what drove the U.S. to pursue the integration of a central bank into their banking system.

In 1907, the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from its previous year peak, causing a chain of events that brought the American economy to its knees over a three-week period. Provoked to a limit, the big bankers at the time gathered in J. P. Morgan’s office to consider the implementation of a central bank.

After about 5 years of discussions on how exactly the Federal Reserve should be structured, in 1913, legislation was passed. The extensive considerations led to the creation of a uniquely-structured central bank, one that would tackle the problem of the repeating panic bank runs and stabilize the economy, while also steadily pushing it upwards.

However, these positive expectations of the Federal Reserve were met with negative side effects. The banking system was now extremely centralized and dependent (to some extent) on the Government. The printing money out of thin air was also something that spurred a lot of worries, spiraling out of control at times as conspiracy theories about the Federal Reserve began concocting a potion of misunderstanding.

While central banks are uniquely structured in the different countries they operate in, they typically have one main purpose – set the monetary policy of the country to help promote national economic goals.

For this article, I will exclusively use the example of the Federal Reserve to help express my opinion on cryptocurrencies and their role in central banking. I believe that, while the structure of a central bank will certainly influence the integration of a digital currency therein, it is not of paramount importance in determining the viability of digital assets in their role of complementing or even replacing the already established system.

The structure of the Federal Reserve

Contrary to popular belief, the central bank of the U.S. is not a single uncomplicated entity, operating out of a castle-like building and completely independent from anything, forging money out of thin air with the sole purpose of controlling society. In fact, it is exactly the convoluted nature of the Federal Reserve that makes it so unique compared to other central banks.

First of all, the Federal Reserve adopts a regional structure, splitting the country into 12 districts. Each of these districts has its own Federal Reserve that oversees the open market operations therein. Next comes the Board of Governors (Federal Reserve Board), comprised of 7 people appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

To ensure that the Federal Reserve is not influenced by short-term changes in the political landscape, the Governors’ terms last 14 years. The Board of Governors is the overseer of the Federal Reserve as a whole, making top-level system operations and regulation decisions.

Each of the Federal Reserve banks in the 12 districts is incorporated as a private company, in a sense. Commercial banks in each district are required to purchase stock equal to 6% of their total capital and surplus. This stock is non-tradeable, cannot be sold, and is valued at a constant $100 per stock. Stocks cannot be purchased by the public and are sold only to private banks who operate within that particular Federal Reserve’s district.

Banks that hold stock in a Federal Reserve appoint 6 of the 9 members of the Board of Directors of that local central bank. The other 3 are appointed by the Board of Governors. In exchange for keeping 6% of their capital in the Federal Reserve, banks are paid 6% dividends yearly. The remaining profits of the Federal Reserve all go into the Treasury.

In 2014, Mitchell Langbert, Ph.D., requested a list of all stockholders in all regions of the Federal Reserve. If you are interested in seeing which companies hold stock in the Fed, you can take a look here. Naturally, it is simply a very long list of member banks.

As an independent entity within the government, the Federal Reserve is extremely profitable, bringing in close to $90 billion to the Treasury in 2012, while paying commercial banks only about $1.637 billion in dividends.

In short, the Federal Reserve is structured in a way that makes it very resistant to political influence, while overseeing a monetary system far more insusceptible to panic and irrational negative feedback loops than its preceding economic scenery.

How the Federal Reserve works

The main goal of the Federal Reserve is to oversee the monetary policy of the U.S.. It does so mainly by conducting open market operations, setting the discount rate, and setting the reserve requirement for commercial banks.

Reserve requirement

Each commercial bank operating in a Federal Reserve district is required, by law, to keep a certain percentage of its assets in cash. For instance, if someone goes to a commercial bank and deposits $1,000 and the reserve requirement is 10%, that bank will put $100 into its own reserve and then invest the other $900.

This is what’s called fractional-reserve banking. The Achilles heel of this kind of system is as apparent as a vulnerability can be. What if people want to withdraw so much money that it crosses the 10% reserves the bank has at hand? In that case, the bank becomes illiquid so it either has to liquidate some of its assets quickly or go to the Federal Reserve (or another commercial bank) and get a loan.

This point is precisely where the system cracked before the Federal Reserve was introduced. Currently, there are three different rates for the reserve requirement imposed on commercial banks:

- Banks with deposits less than $16 million – 0%

- Banks with deposits between $16 million and $122.3 million – 3%

- Banks with deposits of more than $122.3 million – 10%

The Fed doesn’t really like to move the reserve requirement much as a way of lowering/increasing the money supply. That’s because even a slight few percentage change can create a lot of trouble for some banks, especially the ones that play very close around the reserve requirement.

Discount rate

This one is pretty simple – it is the rate at which the Federal Reserve loans money to commercial banks. If a bank needs cash quickly and there is no other viable alternative, they will go to the local Federal Reserve bank and request a loan. The discount rate is the interest rate that the Federal Reserve will charge the commercial bank for that loan.

Typically, the discount rate is always higher than the general rate at which banks loan to each other (federal funds rate). That way banks always prefer to deal with each other and will only use the Fed as a last resort, like in 2008.

As of August 1st, 2019, the Federal Reserve Board has set the discount rate at 2.75%.

Open market operations

While the term sounds complicated, it is actually very simple, and is the main tool the Fed uses to steer the monetary landscape of the U.S.. Every time you hear about the Fed lowering/increasing the interest rates, they are usually talking about the federal funds rate.

The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks loan money to one another. However, while you may think that it is simply a constant the Fed sets, that is not the case at all.

The Fed sets a target for the federal funds rate and tries to attain that target by performing open market operations.

Here’s how it works. Let’s lay the foundation for our example:

- We have Bank A, which has 20% reserves.

- We have Bank B, which has 12% reserves.

- The reserve requirement for both banks is 10%.

- The current federal funds rate is 8%.

- The Fed wants to lower the rate to 7%.

Since the reserve requirement is 10%, Bank B is a bit worried to be so close to the threshold. On the other hand, Bank A doesn’t like having so much cash in its reserve since that is money just sitting around. In that scenario Bank B goes to Bank A and asks them for a loan. Bank B needs cash for its reserve and Bank A needs to loan out some cash to make profit on the interest.

Bank A proposes to loan 4% of its reserves to Bank B at an interest rate of 8%. Bank B is reluctant about that as the interest rate seems a bit high. In comes the Federal Reserve.

What it will do in this case is go out and buy U.S. treasuries, which, to simplify the example, you have some of. So you sell these treasuries of yours to the Federal Reserve (you have no idea who you are selling to, it’s an open market), and you get your cash in exchange. What do you do with that cash? You go and put it into your bank account, which happens to be registered with Bank A.

Then your brother does the same, but he is with Bank B. Let’s say that you both had a lot of treasuries and your recent deposits have now drastically changed our example:

- Bank A now has 25% reserves.

- Bank B now has 15% reserves.

In this case, Bank A is now more willing to loan some of its reserves to Bank B at a lower rate, since Bank B no longer needs that money so urgently. They both agree on a 7% interest rate and complete the transaction.

This extremely simplified example portrays how the Federal Reserve performs open market operations. Naturally, when they want to increase the federal funds rate, they go out and sell treasuries, lowering the total money supply in circulation. In that case money becomes more valuable and the interest rates between banks increase.

Here is a chart of the historical value of the federal funds rate:

The current target for the federal funds rate is 1.75 – 2.00, and it was measured recently at 2.00, compared to the previous 2.25.

Why the Fed cares about interest rates

Effectively, the Fed controls how easy it is to borrow money by lowering/increasing the federal funds rate. That way it either expands or contracts the economy. The goal is to keep inflation in check, not allowing the U.S. dollar to get devalued due to out-of-control borrowing and spending.

Inflation is the increase in prices that occurs when people have more to spend than what’s available to buy. After the 2008 economic crisis, as you can see from the image above, the Fed kept the federal funds rate at practically 0 in order to help promote economic growth. It was only around 2015 that it began increasing the cost of borrowing, as it saw the economy had recuperated, at least to some extent.

Inflation rate of 2% is considered to be the most stable over the long-run. At the moment, the U.S. inflation rate is sitting at 1.7% for the 12 months ended August 2019, which is a 0.1% drop from the previous period.

As the Fed only recently lowered interest rates (from 2.25 to 2.00), it is clear that the current economic goal of the U.S is to boost growth.

Essentially, the Federal Reserve influences the federal funds rate as it is a single point, which, when changed, reverberates through the entire monetary system, thus being the easiest and most efficient way for the Fed to promote national economic goals.

Cryptocurrency and central banking

There’s two schools of thought – either cryptocurrency can be integrated into an existing central banking system (as what’s called a central bank digital currency or CBDC) or it can completely replace a central bank (a far less likely option, although we will take a look at that as well).

But before we get to reviewing exactly how a cryptocurrency can be issued by a central bank (or figuratively act as one) and its potential implications on the current financial system, we need to understand a few things:

- Why cash is disappearing and how that and the rise of Libra have set off an alarm in the central banking community.

- Is a CBDC actually needed? Can it improve monetary policies central banks are currently using to manipulate the economy?

- The current technological solutions central banks have to choose from when specifying the design of a CBDC.

After I lay this foundation needed to make my point, I will proceed to portray how a cryptocurrency can act as a CBDC, specifying the different possible designs, trade-offs between key features, and noting on the advantages and disadvantages when compared to a CBDC not built on top of blockchain or other distributed ledger technology (DLT).

Finally, I will examine the case for a cryptocurrency fully replacing the Federal Reserve, essentially fulfilling the dream of Satoshi Nakamoto and his/her/their goal of eradicating centralized monetary systems.

Towards a cashless society

Cash is clearly losing the battle against the effortlessness and convenience of digital payments. Paying with the touch of a debit card has now become as natural as paying with cash, at least to a younger demographic. Our wallets no longer need to become stuffed full of money coins, taking insufferable space in our pockets and forcing us to waste ours and other people’s time at the cashier, counting the coins until we reach the required sum.

Now we can simply hear the well-established “card read” sound and know that we are done. However, the blooming perks of digital payments have shrouded people, forgetting that cash has great advantages over digital money. In particular, paper money has one very outstanding property – anonymity. And in a world where privacy has been bashed into oblivion, even the slightest manifestation of it warms the heart.

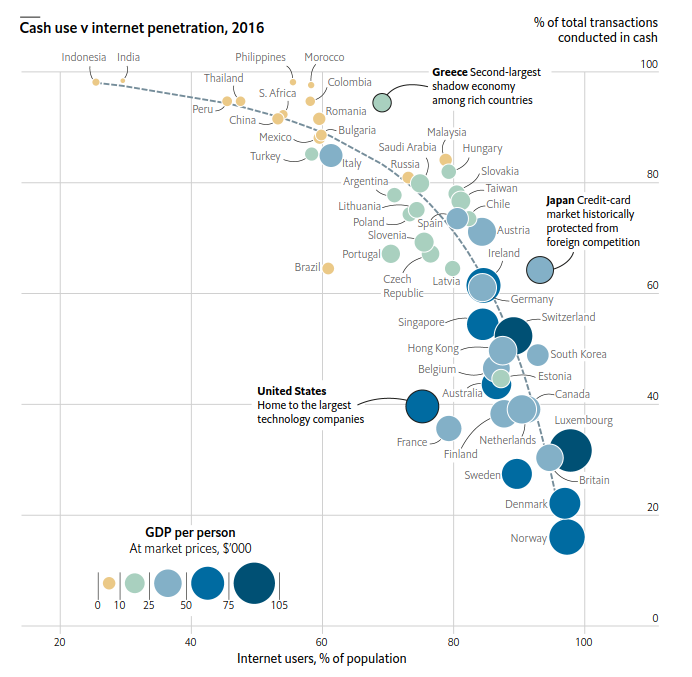

However, the trend is clear:

Norway has already almost “eradicated” cash transactions, currently accounting for only 6% of all trades in the country. In China, digital payments skyrocketed from 4% in 2012 to 32% in 2017. The trend is clear.

That being said, paper money has another great property aside from anonymity – legal tender. Legal tender basically means that, if you are in debt to someone they are required, by law, to accept paper cash as a payment. This gives the Federal Reserve a monopoly in national currencies, effectively standardizing the means of exchange of value in the country i.e. the U.S. dollar.

Leading up to the civil war however, private money was the norm. The problem with private money is obvious – exchange. What if there’s 100 currencies in a country and some merchants accept one of them, others accept another, and so on. It becomes increasingly more difficult to use money as a median for the exchange of goods.

With the instigation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 and the legal tender status of the USD, private money no longer stood a chance.

The U.S. dollar is secured by law to be a safe store of value and is thought of as risk-free since the Government and Fed are considered to be impossible to go bankrupt – something that is very much up for debate as the U.S. debt is slowly spiraling out of control.

With the advent of Bitcoin, a new type of private money spurred into existence. All of a sudden we again had countless currencies into circulation and the similarity with the previous era of banks issuing their own notes is conspicuous.

In that line of thought, the central banks around the world are starting to see cryptocurrencies as rivals in a future cashless society. Stablecoins, and more specifically Libra, have taken governments by surprise, forcing them to rapidly accelerate their efforts in researching, testing, and ultimately implementing CBDC.

In reality, cryptocurrencies, as they currently stand, don’t really pose a serious threat to central banks, being far from the adoption levels that would make them comparable to the big financial institutions. However, quick jumps in capitalization are common in the digital assets market, making the possibility of CBDC competition all the more viable.

Returning back to the properties of paper cash, on the opposite side of the advantages, stands the fact that it is a non-interest-bearing store of value. One dollar is one dollar at the beginning of the week and at the end of it. This creates a list of pros and cons, the latter usually not very popular with people unfamiliar with monetary policy tools.

The pros are obvious – in a time of economic hurdle, people can stash paper cash and wait for the better days to come. The cons deriving from the static face value nature of paper cash are its effective taxation by inflation and a limit on monetary policy central banks try to promote when the economy needs a boost. We will talk about the latter in the next section.

Paper cash being taxed by inflation is a result of the usually positive percentages on inflation, which essentially means that goods and services gradually become more expensive, meaning a hundred dollar bill might not buy you as much at the end of the year as it did at the beginning.

Summarily, paper cash is no longer the prefered payment method in developed countries, creating a trend towards a cashless society. However, some of its properties are valuable, making the case for a CBDC that would gradually replace paper cash, keeping some of its key properties but also improving on some of its disadvantages.

The case for CBDC

The richer countries are leading the cashless economy train, with Sweden already strongly bent on an e-krona, their proposed CBDC. The main motivations of most central banks for implementing a CBDC are:

- CBDC can be the successor of cash in a digital world, embodying key properties of the current paper notes we use.

- CBDC can allow individuals to open accounts directly with the central bank, something that is currently limited only to financial institutions.

- CBDC can fulfill an age-old proposition that cash should bear interest.

- CBDC can improve the way monetary policy is carried out by a central bank by “streamlining” its operations, at least in some forms of design.

- CBDC can make unconventional monetary policy tools, such as quantitative easing, obsolete.

- CBDC can eradicate money laundering and other forms of malicious activity, currently enabled largely by paper cash.

- CBDC can limit the practice of fractional-reserve banking by providing a safer store of value while still paying out interest on deposits.

- CBDC can serve as a medium of exchange (potentially costless), secure store of value, and a stable unit of account.

- CBDC can cause more competition in the wholesale and retail payment systems, challenging the current quasi-monopolistic status of that particular part of the financial industry.

- CBDC could bring access to the monetary system in areas where people don’t have other means of access to banks.

One of the more compelling arguments for CBDC includes its ability, if designed appropriately, to bypass the effective lower bound (ELB) on interest rates, currently “set” by paper money. Here’s a simple example to explain ELB and the problem therein.

Let’s say the economy suffers a severe adverse shock, similar to the Great Recession. In that case, central banks react by lowering interest rates to practically zero, hoping to boost economic growth by making the borrowing of money practically costless.

However, if that doesn’t work as was the case imminently after the 2008 economic crash, central banks can’t lower interest rates much below zero – in some countries they went into negative interest rates, but that was still constrained by the ELB.

The problem is fear. One would think that making the borrowing of money practically costless immediately reverses a contracting economy, with everyone rushing to the banks to borrow money. However, in reality, that’s not how it goes and the 2008 global economic crisis is as solid evidence of that as one can be.

The loss of trust in the financial system forced people to withdraw whatever money they could and stash it in cash wherever they could, in fear of losing everything in extremely uncertain times. As we already mentioned, cash does not bare interest and the central bank has no way of imposing a penalty for holding paper money.

That’s where the idea of negative interest comes in. If central banks could impose a negative interest rate on holding paper cash, then it would theoretically force people to start spending more – no one wants to have their savings taxed for just sitting there.

Nowadays people can easily avoid negative interest rates by holding paper money, effectively stalling the recovery of a contracted economy.

With CBDC, this problem could be solved as digital money could be set up in a way that allows the central bank to set whatever interest rate they see fit to promote economic stability and growth. It could even allow the central bank to laser target its monetary policies only at certain areas, where the economy needs a more radical adjustment.

Furthermore, households with low amounts of savings could be exempt from negative interest rates. Only accounts with deposits over a particular threshold would receive a negative interest rate, forcing the big money back into circulation, thus stimulating economic growth. That of course applies only to a cashless society and countries where there is no wealth tax.

The more popular proposals for CBDC emphasize on its gradual implementation alongside paper money. Eradicating cash overnight is not a desirable solution in any sensible scenario as it will induce a radical change in the monetary habits of people, who are used to paying with paper money.

As the ELB is effectively removed by CBDC and the lack of paper cash in circulation, the interest rate on the central bank digital currency can become the main monetary policy tool used by central banks.

Banks would compete with that interest rate, fighting for the people’s deposits with more lucrative interest rates of their own. That in turn may lower the severity of fractional-reserve banking as people not looking to take any risk on their savings will be able to deposit them directly into the central bank, while still earning interest.

Money laundering and other forms of criminal activity enabled by paper money will become extinct as CBDC becomes more and more ubiquitous. Payments could practically become instant and costless, depending on the technology used for the CBDC.

Furthermore, costs pertaining to paper cash will become a thing of the past since CBDC can be created, distributed, and destroyed at practically no expenditure. For example, the Federal Reserve currently spends 14.2 cents to print one $100 dollar bill. This does not include distribution costs (getting the paper cash to where it needs to go) and security costs (safely storing and distributing paper money). Obviously, these expenses translate to any individual or institution holding cash.

Lastly, CBDC can become the only risk-free anonymous means of exchange of value in a cashless society.

In short, CBDC has a lot of implications, at least on theory, that it can serve as a worthy replacement of paper money, preserving some of its useful features while also building on top with its own unique set of ingredients. As such, CBDC could help improve the effectiveness of central bank monetary policies, eliminate the effective lower bound on interest rates, inject a healthy dose of competition into the banking system, and serve as a costless means of exchange, secure store of value, and a stable unit of account, while also paying out interest equal or close to the one paid on government bonds.

The case against CBDC

While the potential benefits of CBDC might seem obvious, a general counterargument comes along – do we really need a central bank digital currency in a cashless society? Can’t we simply continue using the digital money provided by banks and use cryptocurrency for anonymous person-to-person transactions? In other words, can we thrive solely on private money in a cashless society?

For instance, the effective lower bound on interest rates can be manipulated in other ways, aside from implementing a CBDC. As I already mentioned, holding paper cash, especially in large amounts, can prove to be a costly enterprise.

Additionally, central banks could remove larger denominations of their currency to make it even more difficult to hold huge amounts of paper money. For example, as of April 27, 2019, the 500 EUR note is no longer issued by central banks in the EU area.

An even bigger problem might be the setting of negative interest rates. That is something that the public might not be ready to cope with yet and completely misinterpret. While a zero interest rate might still seem reasonable to people, a negative interest rate could potentially induce thoughts of banks stealing money. Thus, it may take some time for negative interest rates to transform from an anomaly into a normal well-understood monetary policy.

Another potential benefit of CBDC could prove double-sided – its promise to expose access to banking in areas whether other tools are not available. In the richest countries this obviously does not apply – most people there already have easy access to banks, one way or another.

Unpredictable effects on the business models of financial institutions is also something that worries policymakers. With a central bank digital currency, especially one that bears interest, commercial banks would have a new strong competitor. This in turn might lower their revenue as people begin storing their savings with a more trustworthy institution. Subsequently, investments into businesses will slow down as banks experience a drop in capital.

Whether this change will be moderate and healthy or radical and potentially disruptive, is still up for debate. Some suggest that banks will simply adapt their business models to compensate for the reduced number of customers, while others believe that, gradually, banks will become narrower and narrower, adopting the use of what’s called narrow banking (the opposite of fractional-reserve banking), effectively becoming a simple proxy for central banks.

Another major problem with CBDC is security. In a cashless society, the national currency might become extremely centralized in its digital form, opening a discussion on cyber security. A central bank digital currency must be designed with the utmost precision, negating any possibility of malicious activity, something that is quite questionable at the moment.

The progress of quantum computing is also adding uncertainty to the mix, especially in the security of cryptography-based systems.

Lastly, in some forms of design, CBDC could facilitate criminal activity. The trade-off between anonymity and KYC policies could make the difference between a CBDC that suffocates malicious monetary practices and CBDC that enables them even more.

In short, the lack of research and real-life tests adds a lot of unpredictability to central bank digital currencies. A small change in any of its features in pursuit of a specific monetary policy objective could potentially have immense effects on other margins. This uncertainty is healthily holding CBDC back, as central banks try and figure out the best way to do it.

Cryptocurrency as a central bank digital currency

Now that we have laid the groundwork, let’s take a close look at how cryptocurrency (token-based system) can be used as a CBDC and what its benefits are over traditional account-based systems. I will use the Federal Reserve as a base when a specific example is required, the goal being emulating the current structure of the Fed since a radical approach to CBDC could result in extremely unpredictable repercussions.

In its simplest form, a Federal Reserve CBDC, let’s call it e-dollar (from e-krona), will be a cryptocurrency working on a custom consortium-based blockchain, where each of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks will act as a node. This decentralizes the system while still keeping it private, allowing the Federal Reserve to remain the sole entity that sets monetary policies in the country, while also ensuring there isn’t a single point of failure.

Public blockchain issues such as scalability and transaction reversion will be solved as the Fed will have full control over the e-dollar and its underlying blockchain.

As the system is built on top of DLT, a clearing house will be obsolete as transactions will be verified by the Federal Reserve nodes. As opposed to the current system, people will now be able to open accounts directly with the central bank where they would have the chance to exchange their USD for e-dollar and start earning interest.

The first problem comes with anonymity, one of the core values of cryptocurrency. It’s obvious that we can’t have a fully anonymous e-dollar. It will defeat the purpose of extinguishing money laundering and other criminal activities. As a bank, the Fed will have to perform KYC checks on people opening accounts.

However, in the case of a cashless society, all of our transactions will become digitized, either via e-dollar or digital bank money, erasing our trade privacy as a whole. The state will then have full access, direct or indirect, to every person’s entire transaction history.

This problem of privacy has been around for a while now and consists of three main types of opinionated spectrum – first, we have people who go by the argument of “if you have nothing to hide, then what’s the problem?”, secondly, we have people who think that the state should have minimal amount of information on each person in order to run its business, and finally, we have people in the middle trying to balance privacy with individual liberty.

The argument that commercial cryptocurrency, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, will eventually become the only means of anonymous exchange of money is plausible but not practical, at least at the moment. The lack of widespread adoption and the extreme volatility makes Bitcoin and any of its alternatives an extremely unsafe store of value.

Moreover, cryptocurrency’s anonymity is slowly being erased by regulation of crypto exchanges, which are the major gateway to swapping digital assets for fiat currency. After all, you can purchase only so many things with Bitcoin.

The problem with CBDC anonymity could be partially solved by allowing people to withdraw their e-dollar to a local wallet, perhaps on their mobile phone.

This wallet will make it possible for people to exchange money with one another in a semi-private way. However, this in turn will promote criminal activities since malicious actors will now have a way of exchanging value in an undisclosed manner. Furthermore, a number of security concerns arise from people being able to store their e-dollar locally.

What happens if they lose their phone? How secure is it to store digital money on a phone? The trade-off between privacy and law enforcement is a major issue of CBDC implementation, right alongside security.

Bypassing that, the benefits of a CBDC have already been mentioned. With the lack of intermediaries to confirm and verify transactions, the cost of sending/receiving money will become practically zero.

Additionally, transactions will become instantaneous, a huge improvement on the current systems that sometimes take days to confirm and verify an exchange, albeit improvements such as SEPA and TIPS do exist.

Due to the accessibility, effectiveness, and convenience of CBDC, paper money will gradually become obsolete, making the interest rate on the e-dollar a primary monetary policy tool used by the Fed. Not constrained by the effective lower bound on interest rates, the Fed will now be able to go into negative interest rates with ease, forcing the quicker recovery of a contracted economy, at least in theory.

While the effects of CBDC on the commercial banking industry are hard to predict, it is plausible to assume that commercial banks will also adopt the e-dollar, creating more lucrative opportunities in order to remain competitive.

As a security enhancement, the use of narrow banks is suggested in the place of people opening accounts directly with the central bank. Narrow banks would be vetted by the Fed, becoming the proxy for e-dollar issued by the central bank. This additional layering will add cost to the system, but some argue may be necessary as it will add a healthy segmentation to the CBDC system.

To include recent advancements, instead of narrow banks, smart contracts could be created that will act as narrow banks, seeing as their business model is uncomplicated. Smart contracts could also be used to facilitate various other financial instruments and cut down costs and processing times of more complex trading operations. For the time being, smart contracts are out of CBDC-related conversations.

On the other side of the aisle, account-based systems propose a different technological solution to CBDC implementation, similar to the ones currently in place, where we have clearing houses and wholesale and retail payment systems. In that case, central banks have two choices:

- Develop and manage the systems themselves.

- Leave it to the private sector to create solutions.

The latter seems to be the better option as it will invoke competition, forcing the necessary innovation that will result in the best possible product. In that case, the central bank will only deal with issuing and distributing CBDC either directly to people and commercial banks, or to vetted financial institutions (narrow banks) and commercial banks.

The advantage of an account-based system is mainly in its years of practice. Cryptocurrency has been around the block for a decade, but it has only been a few years since it started catching the full attention of the financial sector. However, with $1.5 billion stolen in 2018 from crypto exchanges alone, which amounts to a shocking $2.7 million per day, crypto markets have become infamous for their fraud.

Although the proposal for an e-dollar is not to use a public blockchain, the type of DLT where most of the crypto fraud takes place nowadays, it is still under question whether blockchain technology is evolved enough to become the pillar of central banking. The comfort of systems that have been tried and tested might steer more developed countries towards an account-based CBDC.

The intricacies of the advantages and disadvantages of token-based systems vs account-based systems will surely become more apparent as central banks begin testing different designs of CBDC on a grander scale. Whether they will start being used in a similar manner to what I suggested or they will be adopted in a more cautious manner, e.g. first being tried as a new solution for wholesale payments, then retail, and then as the entire backbone of the central bank, is still anyone’s guess, though a gradual approach is more likely.

As blockchain evolves and newer and better iterations of the technology appear on the scene, in my opinion, the implications for a CBDC built on top of DLT will become stronger. As it stands at the moment, central banks in the richer countries are reluctant to use the token approach, preferring, in most cases, the well-established account-based systems.

Cryptocurrency as a replacement for central banks

Since the advent of Bitcoin, the goal of cryptocurrency has been to eventually replace central banks and the banking system as a whole with a decentralized peer-to-peer electronic cash system, as is the key message derived from the original Bitcoin whitepaper.

For the purposes of this example, let’s say that this does happen. The Federal Reserve goes bankrupt, the government of the U.S. defaults on its debt, and a financial Armageddon is unleashed. Out of the ashes, cryptocurrencies emerge to save the day.

A horde of questions come to mind. Let’s say that Bitcoin keeps its status as the most dominant cryptocurrency and becomes the preferred method for transacting goods and services within the country.

What happens if 51% of the miners decide they no longer like some part of the ecosystem and want to hard fork Bitcoin to upgrade it? What then happens to all retailers who have so far been accepting Bitcoin as payment? Some of them might like the old system, some the new. Which one would they go for? How much money will you be losing on exchanging one cryptocurrency for another every time you go into a store that prefers different cryptocurrencies as a payment method?

I think we got a pretty good taste of all that with the whole Bitcoin Cash civil war. Imagine if Bitcoin Cash was the dominant means of exchange of value in any country. Not a good scenario. People nowadays go mad when the U.S. dollar drops 5% of its value.

Even worse, what happens if a critical vulnerability is discovered in the system and malicious actors exploit it? Are we going to have another hard fork?

A monetary policy set by an algorithm doesn’t look like it can work at the moment. There’s too many moving parts on the table and when an exceptional adjustment is required, public blockchains lack the flexibility to adapt to it as their monetary policy is mob-based.

The only way I can see this working is if the government decides to add legal tender to a certain cryptocurrency and regulates it in a way to control updates. But that kind of defeats the purpose and seeing as central banks are barely able to say anything good about commercial cryptocurrency nowadays, I find this scenario has practically non-existent chances of manifesting into reality, at least at the moment.

Maybe at some point in the future, when public blockchains are far more advanced and all the problems of today are solved, maybe then we will transition into the libertarian dream of a decentralized monetary system.

Summary

Ironically, the technology behind cryptocurrency, having been created with the goal of replacing the banking system as a whole, might become an integral part of that same system. A central bank digital currency could, in theory, provide countless benefits to the monetary system of a country, to name a few, interest-bearing risk-free deposits directly with the central bank, a new host of monetary policy tools, a more stable economy, elimination of the effective lower bound on interest rates, and semi-private transactions in a cashless society.

On the other hand, counterarguments appear, making the case for CBDC non-conclusive, essentially theorizing that private money is all we need to keep going, even in a cashless society.

Complications such as the trade-off between law enforcement and privacy, the technology that should be used, and security are all healthily holding back central bank digital currencies, creating an environment for debate that will help produce better designs.

In the end, the unpredictability of the effects of different specifications of CBDC on the financial industry calls for a lot more exploration on the matter, before developed countries, and especially the U.S., become fully convinced that a CBDC is something they should implement.

Resources

The opinion I have expressed in this article has been formulated after a thorough research into the current available literature on central bank digital currencies, most notably:

- Central bank cryptocurrencies

- Digital currencies, decentralized ledgers, and the future of central banking

- Central bank digital currency and the future of monetary policy

- Central bank digital currency: motivations and implications

- The e-krona and the payments of the future

- Should the central bank issue e-money?

- U.S. digital cash: principles and practical steps

- Other papers publicly available on Google Scholar

- Basic central banking principles as explained by Khan Academy

- Various finance-related videos from the Business Casual YouTube channel

- Wikipedia

- The official Federal Reserve Board website

- Assorted finance conference videos, debating the viability of central bank digital currencies

Blockchain is often hailed as a revolutionary technology set to redefine the digital landscape. While much of the attention is centered around cryptocurrencies and decentralized applications (dApps), the unsung heroes powering this innovation are the servers and infrastructure that maintain the network. At the heart of every blockchain network lies a complex ecosystem of nodes, […]

- Being more prone to taking risks and investing money in new technologies, millennials definitely have a big impact on the global economy.

- With most of the current workforce consisting of millennials, this generation has become the deciding factor behind the success and failure of many industries.

- The number of merchants and businesses accepting digital assets is increasing steadily, and here are some examples of where digital assets can be used.

- Using crypto for payments can differ slightly from fiat systems, but getting started is not too difficult, therefore learning how to handle digital assets is essential in 2023.